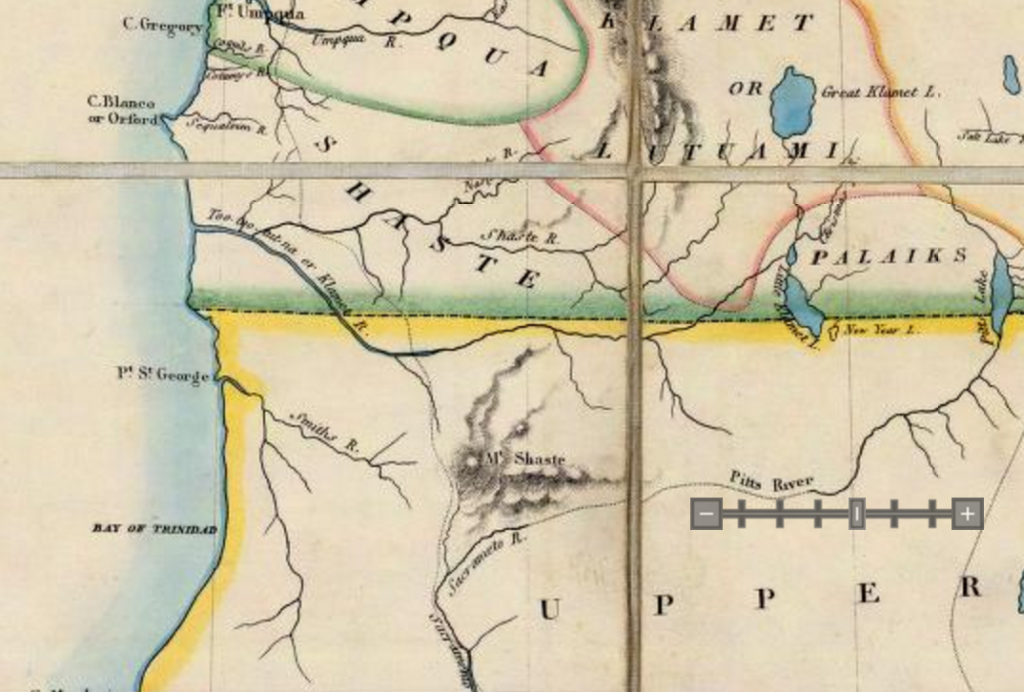

Today’s Daily Create is pretty awesome. It provides an old gold map of the Oregon Territory published in 1844 via the David Rumsey Map Collection, and asks you to pick a spot on the map that would provide the setting of a story. Our job is “to write the opening to a a story that might take place there.” The spot that I immediately gravitated towards was the “Shaste” region.

The Shaste region in the Oregon Territory

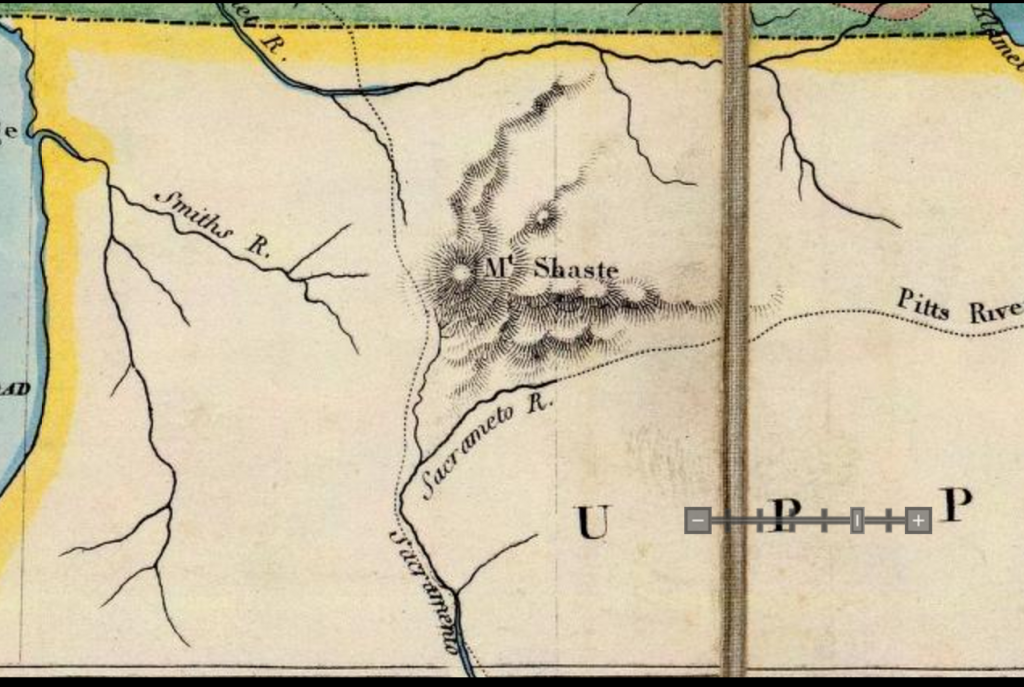

Mt. Shasta in Upper California

Or more specifically, Mt. Shaste in Upper California, or what is now know as Mount Shasta in Northern California 🙂 “Why Mt. Shasta?” you ask. Well, my brother lives in Red Bluff, California, not far from Mt Shasta, and I spent a fair amount of time up there in the 90s. It’s a gorgeous spot at the southern tip of the Cascade Mountain range that runs all the way up to British Columbia. What’s more, that “Upper California” region stills has remnants of the California Gold Rush which brought the first Euro-American settlements into the area. And that provides a beautiful segue way for both the time period, setting, conflict and action of my humble Western tale: “Bring me the Head of Joaquín Murieta.”

But before I write the opening, a little historical context is in order because the other reason I chose Mt. Shasta is because it was one of the settings referred to in a dime novel I read while in grad school by John Rollin Ridge titled The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta (you can find a PDF of the novel here).¹ In fact, this is a novel that has a couple of pretty impressive firsts: first novel written in California and the first novel written by a Native American. The novel frames a pretty interesting moment in U.S. history right after the Mexican American War. This conflict is seldom talked about, and while it only lasted a year and half it resulted in Mexico losing more than half of its national territory, including Arizona, Utah, Nevada, California, and parts New Mexico, Colorado, and Texas. Talk about a land grab! It’s in many ways the final realization of Manifest Destiny, but one piece of a much longer history that had been written in blood for more than three centuries by that point. I think that might be one reason the Western continues to speak to (or is it haunt?) the U.S. psyche—it can provide a bloody reminder of how we got where we are. What’s more, the Mexican American War opens up broader questions about impulses towards imperialism in the early U.S. that often aren’t suggested until the 20th century.

So, in the late 1840s, early 1850s (just a few years after the map prompting this post was drawn) you have California as a newly annexed territory of the U.S., which means you have an intense, shifting border zone with increased conflicts between the European-American speculators and the existing Mexican and Native American communities (who are increasingly seen as subjects of the U.S.). What better setting than the Gold Rush in Northern California to underscore the violence and greed undergirding this expansion! You can start to see it unfolding, right?

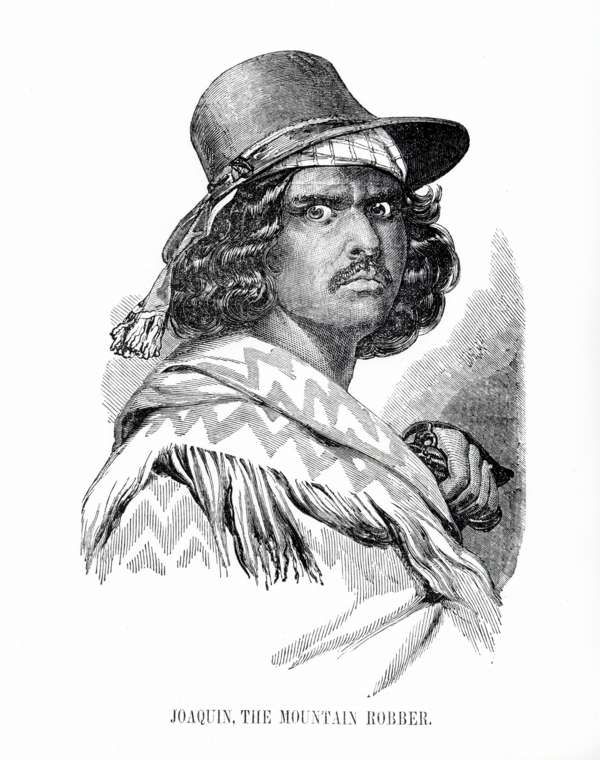

But wait, there’s more. The figure of Joaquin Murrieta (sometimes spelled with one r) is one of legend and lore. Murrieta, once a dignified citizen of Mexico, becomes a legendary bandit after his gold mining claim is violently taken from him. He then takes his revenge on his tormentors. To quote U.S. historian Susan Lee Johnson from Murrieta’s Wikipedia page:

So many tales have grown up around Murrieta that it is hard to disentangle the fabulous from the factual. There seems to be a consensus that Anglos drove him from a rich mining claim, and that, in rapid succession, his wife was raped, his half-brother lynched, and Murrieta himself horse-whipped. He may have worked as a monte dealer for a time; then, according to whichever version one accepts, he became either a horse trader and occasional horse thief, or a bandit

A Portrait of Joaquin Murrieta, “The Mountain Robber”

His wife raped, brother-in-law lynched, and him horse-whipped to within an inch of his life provides an almost textbook example of some of the most horrific violence apparent in a number of contemporary re-tellings of Western tales. And this violence is something Sandy Brown Jensen reacted to in her recent post about the Male Revenge Fantasy specific to this genre of films. And she is right, it’s a story told again and again. After reading Ridge’s novel, I wondered if Clint Eastwood was using it as inspiration for the beginning of one of the most visceral Western revenge fantasies ever: The Outlaw Josey Wales (1974). A film that starts out with the protagonist watching on helplessly as his wife and son are murdered, the blind revenge for which becomes the driving logic of the entire film. Murrieta’s legend provides a very similar case. He went to Northern California in 1849 to find his fortune in the Gold Rush. He encountered racism from the white prospectors, and when the fins out he has struck gold, the miners turned on him and lynched his brother, raped his wife, and nearly beat him to death. After that, he and a band of fellow Mexicans become outlaws and fight the existing power structure, killing numerous European and Chinese-Americans in retaliation.²

A narrative of male revenge fantasy? Yes. But also an allegory for the land grabbing exploits of the Mexican American War, the racism at the heart of Manifest Destiny, and a broader look at the violence that has made our refusal and outrage at it now even possible. Fact is, to tell a tale like Murrieta’s is to be constantly reminded how integral violence was (and is?) to the formation of the U.S. Take, for example, the fact that in 1853 the California legislature hired 20 Texas Rangers to kill the “Five Joaquins“:

The legislature authorized hiring for three months a company of 20 California Rangers, veterans of the Mexican-American War, to hunt down “Joaquin Botellier, Joaquin Carrillo, Joaquin Muriata [sic], Joaquin Ocomorenia, and Joaquin Valenzuela,” and their banded associates. On May 11, 1853, the governorJohn Bigler signed an act to create the “California State Rangers“, to be led by Captain Harry Love (a former Texas Ranger and Mexican War veteran).

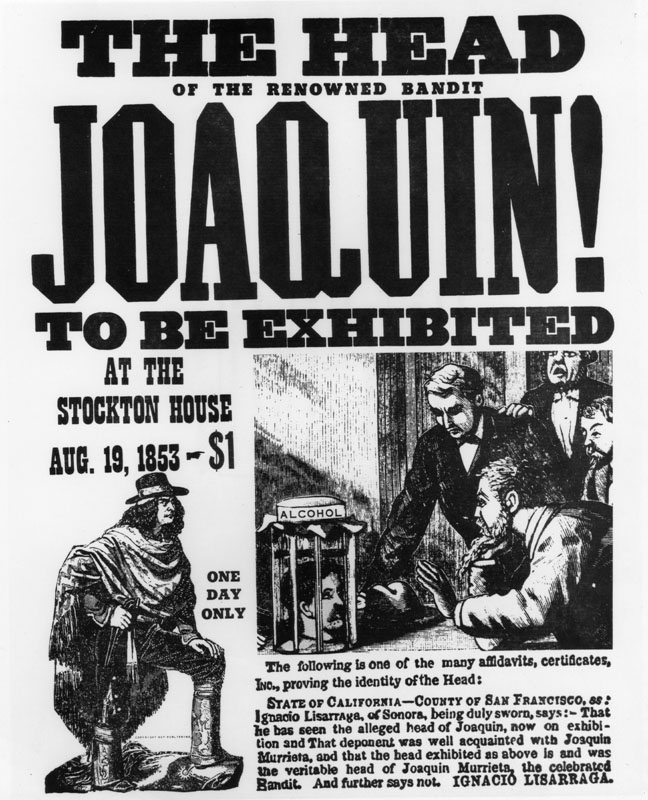

The Five Joaquins could be the subject of a movie in and of itself, add to that the formation of California State Rangers and the manhunt for Murrieta that would, according to legend, ultimately end with his head—preserved in alcohol—being shown for $1 a viewing. It doesn’t get much more violent, and I am just referencing history here.³ The title of this post is inspired by the detail of Murrieta’s head in the Wikipedia article, which makes me wonder if Sam Peckinpah might have been playing on this tradition in another 1974 Western Bring me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (which plays more like a noir than a Western). And whether or not all the facts in legend around Murrieta are true, I don’t think any of us find the details hard to believe if they were, am I right?

A poster advertising the display of the supposed head of Murrieta in Stockton, CA. 1853

As a follow-up to the tale of Murrieta’s demise, the Rangers received the $1000 reward for bringing back his head, but questions about whether the Rangers murdered an innocent and bribed people to swear out affidavits emerged—who needs an imagination when you have Wikipedia? The whole thing is simply crazy, and its hard not to see the violence as part and parcel of this genre given the history it interrogates.

That said, the narrative implications of Murrieta’s story have seemingly endless possibilities for a a revisionist Western, but it also points to the fact that the violence of our past is so easily forgotten in time. I can’t help but think that’s what Cormac McCarthy’s is talking about in his ultra-violent Western novel Blood Meridian when ruminating about the carnage all around one of his characters in the novel:

All about her the dead lay with their peeled skulls like polyps bluely wet or luminescent melons cooling on some mesa of the moon. In the days to come the frail black rebuses of blood in those sands would crack and break and drift away so that in the circuit of a few suns all trace of the destruction of these people would be erased.

All that said, I digress. All I had to do for today’s daily create was pick a point on a map and write the introduction to a story, so here you go:

The scene opens with a shot of Mt. Shasta and the camera pulls out to show a well-built cabin alongside a running stream. It’s an idyllic scene with lush swaths of green and yellow against a striking blue sky embroidered with the Cascade Mountain range in the distance.

Cut to two attractive Mexican men (brother-in-laws, in fact) knee-deep in a stream panning for gold while laughing and telling stories of their exploits in Sonora before heading to “Upper California” to try their luck in the California Gold Rush. They got a jump on the the rush of ’49 that followed later that year, and were able to stake an impressive claim in an out-of-the-way spot on a tributary of the Sacramento River. They have had no luck yet, but that was all about to change, in more ways than one….

Now I want to write the rest of this film. Thank you Daily Create!

______________________________

- Although, truth be told, most of the novel takes place further south in Marysville, San Jose, etc.

- Murrieta’s supposed targeting of Chinese-American immigrants adds another layer of racial and ethnic complexity to the narrative.

- Although, to be fair, history quickly melds with myth in the stories around Murrieta. Turns out his narrative has been attributed, at least partially, to the creation of the figure of Zorro. It’s a rich legend, and I am genuinely surprised more hasn’t been done with it in contemporary explorations of the Western.

Jim,

At one time in my life when I lived in the old inn at Glen Ivy Hot Springs, which is a geologic sister to Murrieta Hot Springs, out on 15 between Corona and Temecula (back road to San Diego), I became obsessed for a while with the origins of a nearby road called Horse Thief Trail. Local rumor had it that the horse thief in question was Joaquin Murrieta, but that turned out not to be true. However, my research on him turned out to be borderline obsessive, and I wrote a researched based fiction piece (“The Corrida of Joaquin Murrieta”) that sorted out the local pieces and retold the story.

It was the joy of the researcher that revisited me again this morning as I read your post, running through my mental fact checker and recalling the richness of that deep investigation. I haven’t revisited that place in my psychic landscape since my delight at the movie The Mask of Zorro, in which Zorro is Alejandro Murrieta, out to revenge the murder of his brother Joaquin. One of my favorite scenes is when Alejandro is in General Love’s office and with great panache drinks alcohol from the glass container holding the head of Joaquin. Yes, it’s another revenge fantasy but one played with humor and the fine art of the sword and that includes a feisty heroine–my kind of Western!

If this is the gold we get for a simple Daily Create I cannot see what you produce for #western106 assignments, definitely bringing back the 10 minute film analysis one for video ( came across one I did a few years ago for “Lonely Are the Brave”).

But this is the kind of digging into stories behind the stories, and their connections / disconnections that I hope goes on. And I never knew you had spent some time out by Mt Shasta, the very feel of the mountains, sky, open land, smallness of the individual cant help but make one feel the west in their bones.

There is something too to be dug into on the role of the horse- introduced by the Spanish, mastered by the Indians, long before the white Cowboys strode in.

Thank you Jim – what a great read. I agree – if this is a daily create wow – Western106 is going to open up a lot of learning!

I also appreciate the balance and telling of the history as looking at it not as “how could someone allow this to happen” and more of what was going on around people for them to make these decisions and actions. What we do need to do is not repeat history and continually look to the innovations and ideas that help us move forward as societies. We can’t apply what we know today to decisions of the past – but we can learn from the past to make better decisions now and in the future. The crime and horror is in repeating the errors and what has been learned to be injustices. We will always continue to fail forward if we are on the right path and fail backwards when we forget to find the lessons learned.

The Bava has provided another six degrees of separation moment Jim – when I worked for the U.S. Geological Survey in the early 80’s I spent a lot of time in the Red Bluff area. We were doing work in the North Elder Creek Chromite mining district and it was a beautiful, lonely place. Alan’s comment about feeling the west in your bones is definitely true.

Hi,

This is very interesting. You’ve just suggested the novel I’ve written, I JOAQUIN, as told by the bandit’s ghost, his head encased in whiskey. If curious, it was recently released in hardcover and paperback from Crossroad Press (Jan. 17) — also available in kindle and soon in audio. You can purchase from their online store or at Amazon: amazon.com/dp/B00LJLQOE0/

And yes, my story fairly much follows the plot you outlined, though with considerable back-story and surreal exploration. In any case, thanks for sharing.

Melvin Litton