I am presenting at Deakin University in Melbourne, Australia in about two hours, and I have been working on my talk pretty diligently over the last 24 hours. It will work in a bunch of my favorite topics such as UMW Blogs, ds106, Domains, and more, but this will be a bit different (or maybe not) given I have been encouraged to speak specifically to what is possible with WordPress. I have been a fairly unapologetic fanboy of WordPress for the last 12 years, so that won’t be hard—plus it is constant source of pride to have picked the winning horse early on 🙂

https://twitter.com/Yanguas1976/status/887813394438422529

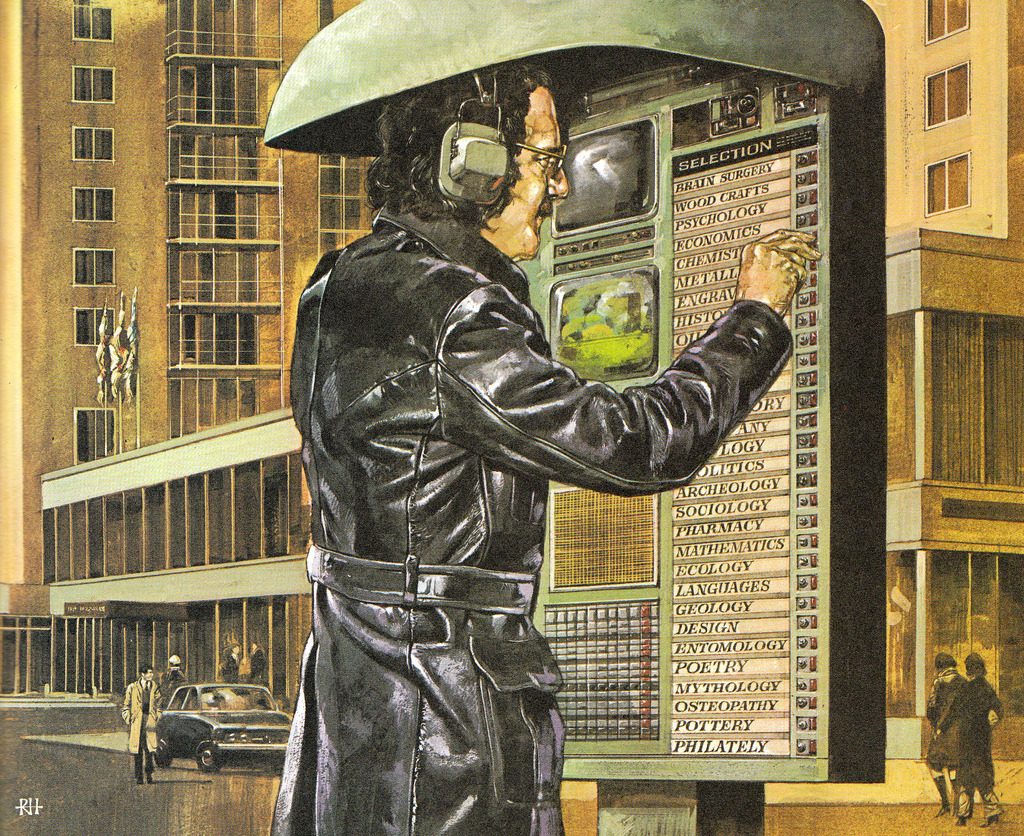

Virtual reality:

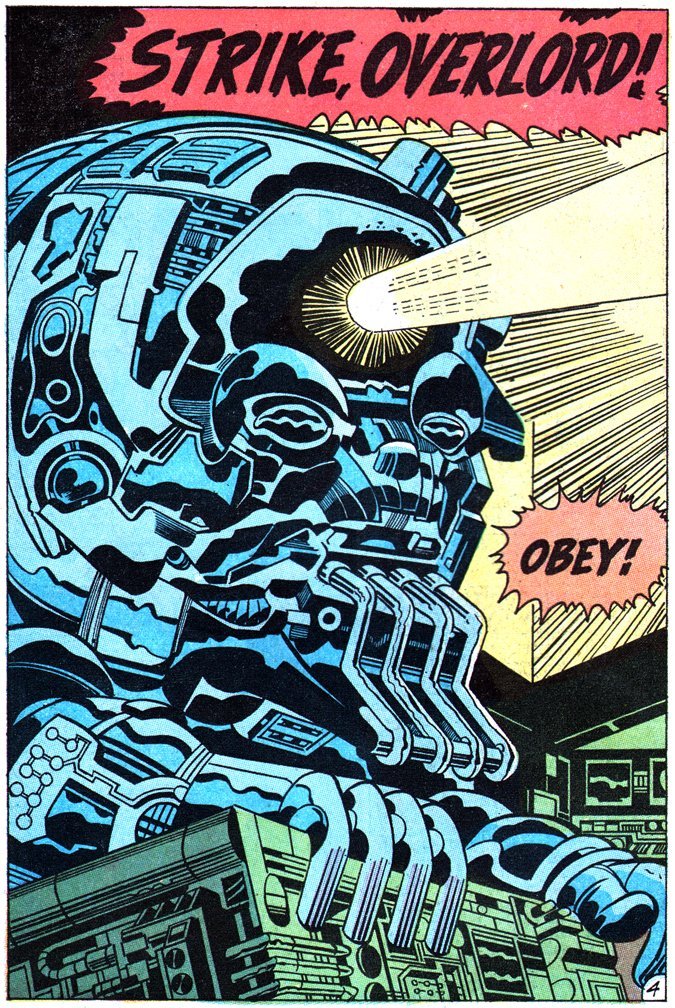

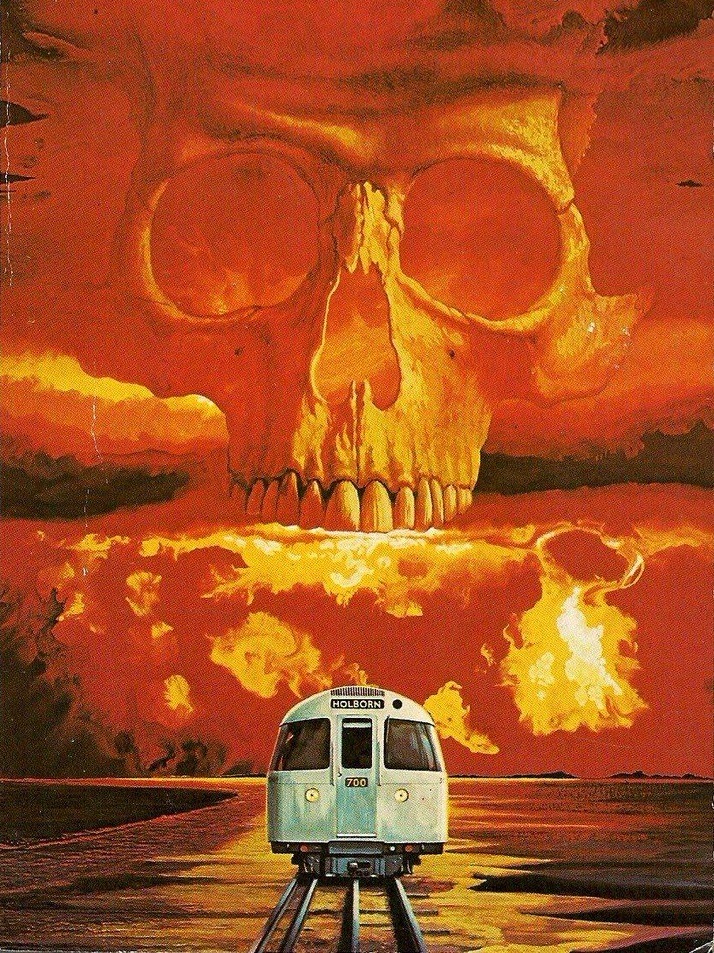

How the shining architectural optimism of the 1960s and 70s has ultimately produced buildings such as supermarkets, open-plan offices and other spaces of control.

This immediately made me think about Audrey Watter’s ongoing crusade as Cassandra for us in ed-tech to understand the transition we are going through, as well as Chris Gilliard’s recent piece in the EDUCAUSE Review, “Pedagogy and the Logic of Platforms” that spells so much of this out so beautifully, Brian Lamb’s reading of Gilliard’s piece (amongst others) frames it well:

Critics such as Gilliard, Cottom, Audrey Watters articulate a wider sense that the web has not only failed to achieve the breathless utopian ideals of a space in which traditional power relationships would be challenged, it is increasingly a mechanism for power to exert itself in ways that were unimaginable until recently. Higher education seems resigned to accepting the fundamental logic of surveillance capitalism as it stands, without asserting competing values or working to address its ill effects.

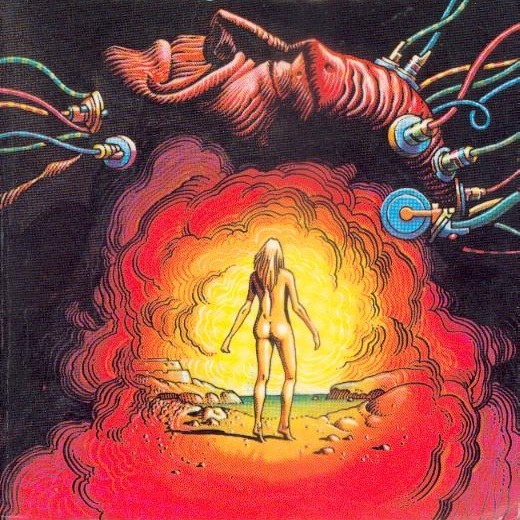

This is our moment in ed-tech, a far cry from the breathless utopia I felt possible in the early stages of Web 2.0, and turns out the spaces we thought we were building for open, expansive teaching and learning were being re-engineered for “personalization,” which is an edtech code-word for mining personal data from students and faculty alike. And this subversion of utopian visions to serve consumerism is exactly what Murphy’s Last Futures seems to argue in the transition from the utopian dream of the 60s and 70s architecture movement to the hijacking of that vision for the late logic of capital:

During the 80s, most of the utopian architectural schemes of the previous two decades were so quickly forgotten or derided – “Nothing dates faster than people’s fantasies about the future,” sneered the art critic Robert Hughes in 1980 – that it was almost as if they had never existed.

As an early Web 2.0 proponent, that hurts.

The flexible, socially responsive sort of building first conceived by progressive postwar architects lives on … but it has mutated into the supermarket, the open-plan office, the distribution warehouse – not usually spaces of liberation but of control.

Anyway, that is where my thinking is for this talk, we’ll see how it goes, but it is a good reminder how crucial aesthetic are for me to make sense of any of this. Might be why Bryan Mathers’ recent NDGLE art is featured so prominently in my slides today 🙂

I love that aesthetic and hope the Deakin folks will dig it too. The metaphor fits well.

Yet I wonder about how far to paint the brush. A lot of that architecture was co-opted, but was it all? And while we can say the same for ed-tech, not all of it was sold out or turned into surveillance capitalism. I don’t dis-agree with the current criticisms, but it starts to sound like everything is the same.

I’d also question that there was a utopian vision back in the Web 2.0 birth years. There was optimism, but was it really gushing blindness? There was excitement, but was it all glib?

And even if you had hints of the vision of today, would that have changed your course?

I feel the same pulse of belief in many of the early ideas, and I will be ****ed if I am going to wring my hands and resign in defeat.

Alan,

Sorry for the late reply here, waking up from vacation and travel this Summer has been a bit hard. I don’t disagree with you on many counts given I try and remain an optimist, but it is also “fun” to go down the hole of despair sometimes with a good metaphor like this. I couldn’t help but be intrigued by the visuals and the story they told about our future which was predominantly dystopian, what’s more so much of that is dictated by the design, which frames our role for edtech as fairly central in this struggle. As timing would have it, I never got much beyond ds106 in the discussion with the Deakin folks, so this point was never really driven home. Not sure if that is for better or for worse, but it seems no matter how hard I try, I still have a hard time dousing the excitement of examples like the Assignment Bank and Daily Create with the dangers of the LMS. It’s almost like once you have seen the possibilities and promise of one approach there is no going back—but that does not help me frame a presentation around 70s dystopian scifi art, now does it?

Pingback: Bildungs Punk at Re:publica 18 | bavatuesdays