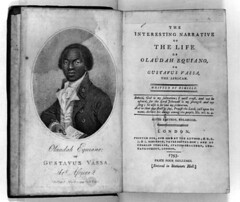

The following passage from Chapter III of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano has stuck with me for well over a decade since I first read this work. And while the veracity of the first three chapters of this work is controversial, Equiano’s narrative is without question one of my favorite Early American texts. The scope of this tale beautifully frames ideas surrounding transnational identities, the mobility of the Black Atlantic, and the anarchic space of the sea. Moreover, it’s an excellent trace of the congealing ideas of racial and national identities during the revolutionary moment of early America. As we see it through Equiano’s eyes, independence and the birth of a new nation of “free men” simultaneously made the institution of slavery, as well as the possibilities of free blacks, that much more oppressive and bleak. The other side of freedom was the increased barbarity towards slaves and the foreclosure of possibility for free blacks. David Kazanjian has a great essay on just this topic, excerpts from which you can find here and all of which you can read here if you have access to Project Muse (and if you don’t, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame for the enclosure of scholarship).

The following passage from Chapter III of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano has stuck with me for well over a decade since I first read this work. And while the veracity of the first three chapters of this work is controversial, Equiano’s narrative is without question one of my favorite Early American texts. The scope of this tale beautifully frames ideas surrounding transnational identities, the mobility of the Black Atlantic, and the anarchic space of the sea. Moreover, it’s an excellent trace of the congealing ideas of racial and national identities during the revolutionary moment of early America. As we see it through Equiano’s eyes, independence and the birth of a new nation of “free men” simultaneously made the institution of slavery, as well as the possibilities of free blacks, that much more oppressive and bleak. The other side of freedom was the increased barbarity towards slaves and the foreclosure of possibility for free blacks. David Kazanjian has a great essay on just this topic, excerpts from which you can find here and all of which you can read here if you have access to Project Muse (and if you don’t, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame for the enclosure of scholarship).

Anyway, all this is a roundabout way to get to the passage from this narrative that I keep coming back to in my mind these days:

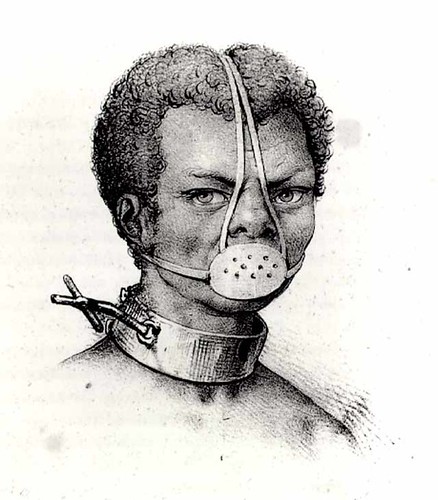

While I was in this plantation the gentleman, to whom I suppose the estate belonged, being unwell, I was one day sent for to his dwelling house to fan him; when I came into the room where he was I was very much affrighted at some things I saw, and the more so as I had seen a black woman slave as I came through the house, who was cooking the dinner, and the poor creature was cruelly loaded with various kinds of iron machines; she had one particularly on her head, which locked her mouth so fast that she could scarcely speak; and could not eat nor drink. I was much astonished and shocked at this contrivance, which I afterward learned was called the iron muzzle. Soon after I had a fan put into my hand, to fan the gentleman while he slept; and so I did indeed with great fear. While he was fast asleep I indulged myself a great deal in looking about the room, which to me appeared very fine and curious. The first object that engaged my attention was a watch which hung on the chimney, and was going. I was quite surprised at the noise it made and was afraid it would tell the gentleman anything I might do amiss: and when I immediately after observed a picture hanging in the room, which appeared constantly to look at me, I was still more affrighted, having never seen such things as these before. At one time I thought it was something relative to magic; and not seeing it move I thought it might be some way the whites had to keep their great men when they died, and offer them libation as we used to do to our friendly spirits. In this state of anxiety I remained till my master awoke, when I was dismissed out of the room, to my no small satisfaction and relief; for I thought that these people were all made up of wonders.

It’s a wild moment wherein Equiano, a young slave who is forcefully taken from his home in Africa to a plantation in Virginia, discovers the technologies of cruelty associated with slavery. Perhaps the most jarring description in the passage is that of the slave woman with the Iron Muzzle, a technology used on a slave if he or she was recalcitrant or was suspected of eating or drinking too much. However, what’s even more sinister is Equiano’s description of technologies like the wall clock and the painted portrait a bit further along in the passage. Both of these objects immediately became instruments of surveillance in Equiano’s mind. He internalizes that which he doesn’t understand as tools of control. It’s the perfect Foucaultian moment and I can’t help to think so many of us remain within this state when it comes to technologies we don’t understand (or even those we claim to), like, for example, the internet. A space that has increasingly become an enclosure of corporate control, and while I desperately hold on to it as potentially liberatory, the ugly side of this technology is that a whole new horizon of surveillance and control is emerging all around us and we are so willingly submitting ourselves to it. We self-police our rights to share, discuss, and re-imagine artifacts like music and movies that have come to frame so much of our cultural identity over the last century. We blindly surrender any and all resistance to an increasingly corporate controlled web. Sometimes I wonder if we aren’t entering a new moment of slavery, a mystified landscape of corporate enclosure that’s designed to preclude alternatives and possibilities to re-think our culture—a constant filtering of our own sense of what’s right for fear of the legal repercussions. The chattel slavery of ideas and ideals, or that particular institution of intellectual property.

It’s a wild moment wherein Equiano, a young slave who is forcefully taken from his home in Africa to a plantation in Virginia, discovers the technologies of cruelty associated with slavery. Perhaps the most jarring description in the passage is that of the slave woman with the Iron Muzzle, a technology used on a slave if he or she was recalcitrant or was suspected of eating or drinking too much. However, what’s even more sinister is Equiano’s description of technologies like the wall clock and the painted portrait a bit further along in the passage. Both of these objects immediately became instruments of surveillance in Equiano’s mind. He internalizes that which he doesn’t understand as tools of control. It’s the perfect Foucaultian moment and I can’t help to think so many of us remain within this state when it comes to technologies we don’t understand (or even those we claim to), like, for example, the internet. A space that has increasingly become an enclosure of corporate control, and while I desperately hold on to it as potentially liberatory, the ugly side of this technology is that a whole new horizon of surveillance and control is emerging all around us and we are so willingly submitting ourselves to it. We self-police our rights to share, discuss, and re-imagine artifacts like music and movies that have come to frame so much of our cultural identity over the last century. We blindly surrender any and all resistance to an increasingly corporate controlled web. Sometimes I wonder if we aren’t entering a new moment of slavery, a mystified landscape of corporate enclosure that’s designed to preclude alternatives and possibilities to re-think our culture—a constant filtering of our own sense of what’s right for fear of the legal repercussions. The chattel slavery of ideas and ideals, or that particular institution of intellectual property.

I’m surprised this didn’t mention the LMSes and badly used Walled Gardens, because that is what I first thought of when reading about the Iron Muzzle.

Have you read The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation? Fiction, National Book Award winner and fascinating look at some of the same issues that Equiano raises, though set at the time of the Revolution.

@Steven,

I was going to mention LCMSs 🙂

@Jeff,

Nope, I haven’t read this yet, but I am gonna pick it up. I am re-visiting a lot of these narratives lately, and i would love any and all recommendations.

I love it when you bring me back…That class seems like another life.

If we’re busy making book recommendations, you should definitely check out Imperium in Imperio by Sutton Griggs if you aren’t already familiar with it. It’s been more than a decade since I read it, so I’m fuzzy on the details, but it tells the story of a separate African-American government set up within the U.S. There’s quite a bit, if I remember correctly, about assimilation vs. overthrowing the (white) power structure. An interesting read!