Disclaimer: This is a “media-enhanced” version of a paper I wrote in graduate school for an American Studies course back in 2002. And while I recognize it is both rough and theoretically meager at certain points, I’m still fascinated with the overall premise of the argument, namely that through movies one can actually trace the changing face of a city like New York over the course of a decade. I was prompted to publish this paper in particular because of a recent conversation I had with Brad Efford about Nighthawks in the comments of this post. Additionally, I am increasingly persuaded that the blog is the ultimate form for framing a visual/media-based discussion around films, and embedding clips that are discussed just make the experience that much cooler in my mind. My writing is admittedly far more formal and restrained than it usually is on the bava, a format I am glad to be free of. Yet, at the same time, I think the paper structure forced me to spend more time building and unpacking a more complex framework of thought for imagining the “Urban Jungle” films of the 1980s. Anyway, this is a long, long post which I imagine few, if any, will read, but I believe it is very much inline with the genesis and ongoing logic of my thoughts on bavatuesdays, so why not make it part of the archive–I am my own publishing house after all 😉

A younger Homer Simpson on the run from pimps and CHUDs

Oh Homer, of course you’ll have a bad impression of New York if you only focus on the pimps and the C.H.U.D.s.

Marge Simpson, from “The City of New York vs. Homer Simpson”

Marge Simpson, with her acute and poignant insight, may have already put her finger on the main point of this paper, making my own ideas somewhat obsolete – but in an attempt to live life in spite of The Simpsons, I will proceed. Focusing on “the pimps and the CHUDs” is exactly what this paper will do in an attempt to suggest the means through which movies during the 1980s “prophesize” the growing momentum of urban transformation (or gentrification) in New York City that we all can bear witness to today. In fact, the recent gentrification of NYC is assumed in this paper. What remains open for question is whether or not we can read the relatively recent “revival” of neighborhoods like Lower East Side, Times Square, Hell’s Kitchen, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Park Slope, and the South Bronx (to name just a few) through a selection of movies that were made during the 1980s. Moreover, if this relationship can be established, than how do we interpret these films’ assorted reflections of the social, economic, and political transformations of the gentrification (a.k.a. “recycling,” “renaissance,” “renewal,” and “revitalization,”) of the inner city? This last question is a much more difficult one, for which I will employ theories of Popular Culture and Marxism to read the methodology of American Studies as well as the contemporary cultural form of urban movies during the 1980s.

When writing an American studies paper on urban Movies and gentrification, it might prove useful to establish how the theoretical models of Marxism and Pop-Culture relate to the discipline of American Studies more generally. Michael Denning, in his essay “‘The Special American Conditions’: Marxism and American Studies,” traces the bibliographic history of Marxism within American Studies, recognizing that while Marxist ideas and frameworks were often borrowed for utilitarian scholarly purposes in American Studies, there have been “few Marxists interpreting American culture: American cultural history has not yet seen the ‘revisionist’ historiography that marks American diplomatic, labor, and social history” (357). Denning asserts that the majority of interpretations of American Culture do little more than graft ideas from Marxists such as Antonio Gramsci, Mikhail Bahktin, and Walter Benjamin, onto their scholarship, avoiding any sustained dialogue with Marxism. Denning argues that the tradition of American Studies, rather than reflecting a strain of Marxism in the U.S., serves as an antidote for continental Marxism (360).

For Denning, any form of American Marxism is preempted by American Studies with its roots in the exceptionalist paradigm that characterizes much of the work of the early scholars in the discipline such as Perry Miller, F.O. Matthiessen, and Henry Nash Smith, to name just a few. America, under the exceptionalist paradigm, is constructed as uniquely insulated from the European threat of Marxism due to, among other things, its resources, geographical isolation, excess land, contented labor, etc. Denning contends that the notion of American Exceptionalism is the work and foundation of the discipline of American Studies, arguing that the major myths and symbols that help define the unique qualities of America are still in wide academic circulation today, namely the figure of the frontier; the Puritan legacy; the anomaly of slavery; and mass consumer culture (360). Denning both indicts American Studies for its provincial myth production while simultaneously recognizing more contemporaneous work in the field that is trying to revise the myths and symbols of the exceptionalist paradigm through a more rigorous Marxist methodology.

Denning’s reference to the place of mass consumer culture within American studies brings us to more specific Marxist approaches to culture such as those of the Frankfurt School. Theodor Adorno and Max Horkenheimer’s The Culture Industry is one of the earliest and most influential Marxist interpretations of the forms of mass culture. This text portrays the culture industry as a mode of production that obfuscates the real relations between capital and labor through mass forms of cultural illusion and disinformation such as Hollywood movies, radio, popular music, and mass journalism. And while this thesis was, and still is, important to the understanding of popular culture, it has subsequently been critiqued for reinforcing strict definitions of high and low culture that rule out potentially subversive readings of a Hollywood movie, for example.

The Marxist critique of culture moves from Frankfurt, Germany in the 1930s and 40s to Birmingham, England in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, where the Center for the Study of Contemporary Culture (and its theoretical brainchild Cultural Studies) builds upon Marxist critiques of culture. This school is recognizable for introducing a sufficiently complex and nuanced critical approach to popular culture by analyzing the various incarnations within contemporary culture. Stuart Hall, one of the Birmingham School’s more prominent theorists, attempts to ground the often too vague and misused definition of Popular Culture in his Essay “Notes on Deconstructing ‘The Popular’.” Hall’s essay offers a more complex understanding of the relationship between popular culture and the forces of power within society (what he terms the “power-bloc”), by tracing the uneven relationships between a center of power and those that it marginalizes. Hall, in attempting to reclaim the term popular so that it might reflect a more specific and complex meaning, defines it as follows:

It is a conception of culture which is polarized around this cultural dialectic. It treats the domain of cultural forms and activities as a constantly changing field. Then it looks at the relations which constantly structure this field into dominant and subordinate formations. It looks at the process by which these relations of dominance and subordination are articulated. It treats them as a process: the process by means of which some things are actively preferred so that others can be dethroned. It has at its center the changing and uneven relations of force which define the field of culture – that is, the question of cultural struggle and its many forms. Its main focus of attention is the relation between culture and questions of hegemony. (235)

As Hall notes, the idea of popular most be understood as a constantly changing process that is engaged in a struggle between the dominant forms and those that it subordinates. Moreover, these popular cultural forms, far from being consistent or stable, are themselves contradictory allowing for changes within an object’s cultural valence over time. As Hall states, “What matters is not the intrinsic or historically fixed objects of culture, but the state of play in cultural relations: to put it bluntly and in over-simplified form – what counts is the class struggle in and over culture” (235). Hence, the process of the struggle itself is always paramount to the cultural object in which it may be reflected. In fact, what Hall does not overtly suggest, but seems to imply, is that the play of cultural relations allows for subversive interpretations of dominant culture. In other words, the interpretation of popular cultural objects acts as a site wherein the process of class struggle can be acted out between the dominant culture and those it subordinates.

While Michael Denning’s push to revise the exceptionalist myths of America through a Marxist lens serves as the ideological challenge for American studies, Stuart Hall’s definition of the play of popular cultural forms provides a methodological framework through which to read the dialectical struggle between the dominant and the subordinate within the culture. Finally, it may be useful to discuss Neil Smith’s interpretation of the relationship between urban gentrification and capital that elaborates a historically and socially specific analysis of the processes of gentrification within New York City over the last thirty years.

[openbook booknumber=”041513255X”] Neil Smith’s The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City brings Denning’s call for a Marxist revision of American myths together with Hall’s attention to the contradictory, and often mutable, significations of popular cultural forms. Smith reads the gentrification of the urban landscape of New York City’s Lower East Side on two levels. First, Smith—picking up on one of Denning’s categories of American exceptionalism—illustrates how the figures of the American frontier are employed to represent and narrativize the gentrification of New York City’s lower income neighborhoods. After restating the importance of Frederick Turner Jackson’s thesis to reinforce the ideological power of the frontier to shape images of American opportunity and expansion, Smith points out in his introduction:

During the latter part of the twentieth century the imagery of the wilderness and frontier has been applied less to the plains, mountains, and forests of the West – now handsomely civilized – and more to US cities back East. As part of the experience of postwar suburbinazation, the US city came to be seen as an “urban wilderness”… the city was rendered a wilderness, worse, a “jungle” … in the language of gentrification, the appeal to frontier imagery has been exact: urban pioneers, urban home-steaders and urban cowboys became the new folk heroes of the urban frontier. (xiii-xiv)

Smith traces how the rhetoric of the frontier is re-inscribed upon cities such as New York in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s in order to suggest the political employment of the figure of the frontier to disinvest the working class neighborhoods of the inner city.

Secondly, in the methodological spirit of Stuart Hall, Smith explores the means through which popular rhetoric such as “urban pioneer” or “urban home-steader,” represent the struggle between the dominant and subordinate within a culture. Reading into the historical figure of the pioneer can suggest the cultural dominance and violence of such a term, reflecting a “civilizing” process at the expense of the “natives” and the “savages.” Reading the process of gentrification through the lens of the frontier focuses not only upon the tainted historical legacy of the 17th, 18th and 19th century American pioneers, but also reestablishes these cultural struggles within the contemporary inner city. In this way, the figures of the frontier that have been traditionally read as positive signs of civilization, cultivation, and renewal, can equally be inflected by cultural supremacy, a raping of the land, and genocide. Therefore, as Stuart Hall suggests, the rhetoric of the frontier, far form being unilaterally oppressive, opens up a dialectical play between figures of the frontier within a historical and cultural framework that allows for a radical revision and subversion of such images as the rugged, individualist pioneer reclaiming the inner city in the name of civilization and progress.

And while the rhetorical and ideological site of this discourse is an important platform for the playing out of this conflict within popular cultural forms, Neil Smith offers another layer to consider when discussing the phenomenon of gentrification in the inner city:

As with every ideology, there is a real and partial if distorted basis for the treatment of gentrification as a new urban frontier. The frontier represents an evocative combination of economic, geographic and historical advances, and yet the social individualism pinned to this destiny is in one very important respect a myth. Turner’s frontier line was extended westward less by individual pioneers, homesteaders, rugged individualists, than by banks, railways, the state and other collective sources of capital. (xvi)

Smith’s attempt to debunk the myth of rugged individualism, or the “first pioneer,” clears space for the examination of the role of capital within urban gentrification. And while the economic expansion of the railroads and banks in the 18th and 19th century was driven by outward appropriation and expansion, the gentrification of the inner city is premised on internal differentiation of already developed spaces. Through this distinction it becomes clear that the narratives of the “urban pioneers” who reclaim a city block in New York’s Lower-East Side as an act of individual will might belie the larger actions of “collective owners of capital” (xvi). In fact, the individual pioneers in the new urban frontier often go bravely where banks, real estate developers, small and large-scale lenders, retail corporations, and the state have all gone before.

In this way, Smith critiques the rhetorical employment of traditional myths and symbols within American popular culture, as well as the economic processes of the inner city that these popular figures serve to understate or elide. In short, according to Smith, during the movement of capital, investment chases the space wherein in it finds the greatest potentiality for productive investment, or the greatest profit potential. So once the threshold of an investment’s return is reached in the post World War II urban center, for example, investment capital flees the city, along with a majority of the middle and upper classes. Following such an exodus of capital, a more protracted period of dis-investments begins throughout the inner city. This urban divestment leads to financial institutions redlining certain districts (i.e. deciding that loans for new development in certain urban areas are no longer profitable), and inducing the depreciation of property values as well as the inevitable de-valorization of entire neighborhoods. In many ways, this process leads to the ghettoization and physical abandonment of the inner city, exemplified (and reflected on film, as we will soon see) in New York City by the escalated disrepair and disenfranchisement of several neighborhoods during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Yet, the devaluing of the inner city is often followed up with a re-investment within neighborhoods that have been stripped of their property value and redlined by banks. Such land offers prime re-investment opportunities for developers and banks within urban centers, allowing capital to reclaim historic or “renewed districts,” laying the groundwork for a triumphant, and often immensely profitable, return of capital to New York City during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Capital’s flight from and subsequent return to the city is important for placing the films I will discuss within a more protracted cycle of urban investments and dis-investments. As Stuart Hall asserts, critical work within the realm of popular cultural forms needs to contextualize the political, economic, and historical factors of a particular cultural phenomenon in hopes of offering a more developed cultural framework, as well as an alternative to more conventional explanations of these processes. In the case of gentrification, the conventional cause and effect narratives might be as follows: the baby-boomers returning to their roots in the city; the emergence of an upper-middle class whose lifestyle of consumption, career, and pioneering made the return to the city an obvious choice. The idea of gentrification as a consumption-side phenomenon that can be explained in terms of “who moves in and who moves out,” equating the city-wide transformations of neighborhoods and rent levels to a rather innocuous and neutral “matter of individual preference,” offers an incomplete and relatively surface explanation of the gentrification process while simultaneously minimalizing the devastating effect such a wholesale dispossession of neighborhoods has on the lower-income inhabitants of New York City. As Smith suggests, “Gentrification is a back to the city movement all right, but a back to the city movement of capital rather than people.”

The revitalization of Times Square has been a well-publicized and often contested urban renewal project that has gained momentum as a sign of the transforming city during the 1990s. However, the political and economic history predates this period by almost twenty years. But rather than reading the metamorphosis of Times Square through the civic history, it would align more with the objective of this paper to take a look at a movie that uses the corporate and civic takeover of Times Square as a backdrop for a father-daughter generational/ideological gap narrative. The movie Times Square (1980) from the moment of the opening credits, foregrounds the forces of urban transformation at work upon the “crossroads of the world.” The beginning sequence tracks along 42nd street picturing the X-rated movie theaters, drugged-out street dwellers, prostitutes, and finally rests upon a “Reclaim the Heart of the City” poster before a man in a suit walking out of a transformed theater/peepshow with a scale-size model of the “new” Times Square (as we learn later on). During this sequence, which captures the variegated landscape and faces of Times Square in the early 1980s, the overlaying Disco music is slowly giving way to Nikki’s (the heroine, who is a musician and independent street urchin) discordant, feed-back driven guitar playing that ultimately drowns out the Disco music of the 1970s. Nikki’s punk guitar becomes an anti-establishment/anti-renewal form of individual expression, a cultural relationship that Punk establishes more strongly in the Tompkins Square Park Riot in 1988.

The revitalization of Times Square has been a well-publicized and often contested urban renewal project that has gained momentum as a sign of the transforming city during the 1990s. However, the political and economic history predates this period by almost twenty years. But rather than reading the metamorphosis of Times Square through the civic history, it would align more with the objective of this paper to take a look at a movie that uses the corporate and civic takeover of Times Square as a backdrop for a father-daughter generational/ideological gap narrative. The movie Times Square (1980) from the moment of the opening credits, foregrounds the forces of urban transformation at work upon the “crossroads of the world.” The beginning sequence tracks along 42nd street picturing the X-rated movie theaters, drugged-out street dwellers, prostitutes, and finally rests upon a “Reclaim the Heart of the City” poster before a man in a suit walking out of a transformed theater/peepshow with a scale-size model of the “new” Times Square (as we learn later on). During this sequence, which captures the variegated landscape and faces of Times Square in the early 1980s, the overlaying Disco music is slowly giving way to Nikki’s (the heroine, who is a musician and independent street urchin) discordant, feed-back driven guitar playing that ultimately drowns out the Disco music of the 1970s. Nikki’s punk guitar becomes an anti-establishment/anti-renewal form of individual expression, a cultural relationship that Punk establishes more strongly in the Tompkins Square Park Riot in 1988.

If you watched the whole clip, you will have noticed that the opening credits are followed by the deputy mayor’s (David Pearl) address to the city council. Pearl’s speech immediately establishes the rhetoric of “reclaiming the X-rated city from the streets,” or in some way, reclaiming what is always already “ours” in the first place. This notion of outraged, law-abiding citizen’s reclaiming the streets of New York City and re-establishing the “the great white way” (which Pearl does not say himself, but is rather diplomatically exclaimed by Pearl’s African-American colleague) is what Neil Smith defines as the “Revanchist city”:

Revange in French means revenge, and the revanchists comprised a political movement that formed in France in the last three decades of the nineteenth century. Angered by the increased liberalism of the Second Republic, the ignominious defeat to Bismarck, and the last straw, the Paris Commune (1870-1871) in which the Paris working class vanquished the defeated of Napolean III and held the city for months – the revanchists organized a movement of revenge and reaction against both the working class and the discredited royalty. This movement was as militarist as it was nationalist, but also made a wide appeal to ‘traditional values’ … it was a right-wing movement built on populist nationalism and devoted to a vengeful and reactionary retaking of the country.

Smith re-inscribes this historical movement back upon the reactionary claims against the “liberalism of the 60s and 70s” to “retake the city,” or “clean up our lost streets,” arguing that this rhetoric strategy is not only aimed at the more dangerous elements of a society, but at a much larger racially and ethnically diverse working class that inhabits the city. Moreover, this constituency is being victimized and removed in the name of “reclaiming the heart” of a new city that they will not have the means to enjoy. Such rhetoric can be viewed as one method of stifling any discussion of the more surreptitious return of capital that accompanies the great white way. This illustrates one of the most instructive elements of these urban movies during the 1980s, they not only capture and reflect on film the physical and cosmetic changes of specific parts of the city at a particular moment in time, but they also rearticulate the social, economic, and political rhetoric surrounding a more popularized logic of gentrification.

The rhetoric of family and decency that Pearl uses here, i.e. the X-rated city not being congenial for the upper-middle class, “especially those of us with kids,” sets up the narrative trajectory for the rest of the movie. Pearl’s daughter later on meets up with the street urchin Nikki, and they run away together and live in an abandoned building on the Chelsea Pier, depicting an absurd domestic bliss of the life of the homeless and disenfranchised: little Pearl becomes a dancer at a strip joint who doesn’t have to take off her clothes, while Nikki establishes herself as an iconoclastic punk rocker. Eventually, their story leaks out vis-à-vis a socially conscious D.J. (Tim Curry) and they become celebrities, name themselves “The Sleaze Sisters“ and sing a song to Deputy Mayor Pearl over the local airwaves, in fact, one of the most perverse songs I’ve yet to hear in a movie (“Spick, Nigger, Faggot, Bum, your daughter is one”).

This song and its admittedly offensive politics of inclusion subverts deputy mayor Pearl’s earlier ideas of reclaiming the streets and making Times Square safe for families, for here his daughter is part of the very thing he is trying to erase. Ironically, at the end of the movie “The Sleaze Sisters” put on a performance, which in many ways exemplifies the very process of gentrification the movie seems to be speaking out against. The DJ publicizes “The Sleaze Sisters’s” show on top of the “Reclaim the Heart of the City” theater in Times Square. The concert announcement is then followed by an extended scene of suburban girls dressing up in their punk regalia and heading to Times Square, acting out the return from the suburbs that will serve to characterize the next two decades of New York City’s urban transformation (interestingly enough, it is a counter-cultural event such as punk, and its affiliation with the city, style and music that affords the opportunity for a new generation to return to the city).

While Times Square uses the family drama to reflect and enact the struggle over the rapidly changing city, The Warriors (1979) offers us another lens on this phenomenon. The Warriors has been classified as an “Urban Jungle movie,” a new genre that many believe has emerged as a means to both fetishize the inner city as well as reinforce the moral depravity and utter lawlessness that our once “civilized” urban centers have been reduced to in recent times. Yet, all of these movies offer a more complex image of the city than such reductive readings suggest, despite the fact that that they do, indeed, reflect a hostile and in some ways horrific urban landscape. And while the decay and defacement of New York City in The Warriors reflects an apocalyptic urban environment, it must be remembered that the eponymous Coney Island gang is traveling 26 miles to Pelham Park in the Bronx (along with close to 10,000 other assorted gang members) to hear their leader Cyrus discuss nothing less than a unification amongst gangs of all races, ethnicities, and creeds in order to reclaim the city for their own purposes – “Can you DIG it!” as Cyrus shouts. In fact, during his speech Cyrus is portrayed as an almost religious figure, whose political ends and oratory might be reminiscent of many of the African-American activists of the 1960s and 70s. Yet, Cyrus’ message proves so dangerous and revolutionary within the film that he has to be assassinated for the much anticipated gang violence and social anarchy to continue throughout the remainder of the film. This proves to be an interesting commentary upon the subversive qualities of these movies. While Cyrus is ultimately assassinated and the gangs continue to remain unorganized, the revolutionary possibility that disenfranchised gangs of all races, ethnicities, and religions can be organized along a common thread of social justice and equality introduces a radically different reading of the Urban Jungle movie above and beyond some simple reflection of the moral depravity of inner city inhabitants.

While Times Square uses the family drama to reflect and enact the struggle over the rapidly changing city, The Warriors (1979) offers us another lens on this phenomenon. The Warriors has been classified as an “Urban Jungle movie,” a new genre that many believe has emerged as a means to both fetishize the inner city as well as reinforce the moral depravity and utter lawlessness that our once “civilized” urban centers have been reduced to in recent times. Yet, all of these movies offer a more complex image of the city than such reductive readings suggest, despite the fact that that they do, indeed, reflect a hostile and in some ways horrific urban landscape. And while the decay and defacement of New York City in The Warriors reflects an apocalyptic urban environment, it must be remembered that the eponymous Coney Island gang is traveling 26 miles to Pelham Park in the Bronx (along with close to 10,000 other assorted gang members) to hear their leader Cyrus discuss nothing less than a unification amongst gangs of all races, ethnicities, and creeds in order to reclaim the city for their own purposes – “Can you DIG it!” as Cyrus shouts. In fact, during his speech Cyrus is portrayed as an almost religious figure, whose political ends and oratory might be reminiscent of many of the African-American activists of the 1960s and 70s. Yet, Cyrus’ message proves so dangerous and revolutionary within the film that he has to be assassinated for the much anticipated gang violence and social anarchy to continue throughout the remainder of the film. This proves to be an interesting commentary upon the subversive qualities of these movies. While Cyrus is ultimately assassinated and the gangs continue to remain unorganized, the revolutionary possibility that disenfranchised gangs of all races, ethnicities, and religions can be organized along a common thread of social justice and equality introduces a radically different reading of the Urban Jungle movie above and beyond some simple reflection of the moral depravity of inner city inhabitants.

[openbook booknumber=”0253209668″] First a quote from a footnote in Fredric Jameson’s The Geopolitical Aesthetic, which while a bit dense when tracing a theory of cognitive mapping and the idea of imagining global space in cinema (I imagine the real point of the book I am missing), has a bunch of interesting readings of some great movies. I particularly liked Jameson’s reading of Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983), which might be a very interesting film to re-watch these days to think about the questions of media, power, control, and psychotropic conspiracy. He also has a great reading of the paranoia films of the 70s, with an intriguing discussion of filming the spaces of power and capital using Pakula’s All the President’s Men (1976) as a fascinating example. Anyway, the footnote in question is a throw away thought Jameson had, that I found both interesting and relevant to this paper:

I have here omitted gang war films, which, at least during a certain period might well have been read as visions of internal civil war, see, for example Escape from New York (Carpenter, 1981), The Warriors (Hill, 1979) Fort Apache, the Bronx (Petrie, 1981). On my view these films shade over into what is called, in Science-Fiction terminology, ‘near future’ representations and this distinctive genre in its own right, its form and structure sharply distinguished by the viewer from ‘realistic’ verisimilitude or immanence. (The Geopolitical Aesthetic, Pg 83 note 15)

I think this quote initially struck me because it references three movies that I loved. And more than that, it gathers them together as a particular genre with the suggestion that they may reflect a vision of “internal civil war” in urban centers like New York City. In fact, it is the idea of an internal civil war that Jameson suggests here, that has informed the way I think about much of the urban jungle films made from the 70s and 80s through the 90s and up and until now. They often reflect a kind of struggle at work within the invisible underworlds and subcultures of any given city that is akin to a city at war with itself, factions of power (wealthy developers, the agents of gentrification, the minions of capital) versus those being marginalized, displaced, and dis-empowered. This struggle brings me to one of the most important and powerful elements of The Warriors, and what I firmly think marries a revolutionary message with an unbelievably cutting edge and imaginative aesthetic that reflect the times. The gangs make this movie, when I first watched the Warriors in the early 80s we were all intrigued by the gangs and their crazy get-ups. There was something for everyone: the Turnbull ACs were the skinheads; High Hats played Soho artist thugs; the Gramercy Riffs married Black Panther militarism with some impressive kung-fu (long before the emergence of the WuTang clan); the Baseball Furies whose psychotic face paintings were only outmatched by their Yankee pinstripes and Louisville Sluggers; and we shouldn’t forget about the Lizzies who were a band of “badass chicks” who my four sisters immediately related to and started imitating. The gangs’ outfits, their territorial presence, and the fact that the beginning of the movie brings them all together in one place, frames the hopeful, revolutionary moment of this internal civil war.

Fort Apache, the Bronx (1981), unlike The Warriors and Times Square, concentrates upon the struggles of two cops on the hostile urban frontier of the South Bronx. The tag line for the movie establishes the figures of the Western frontier if you somehow missed the allusion in the title, “No Cowboys, No Indians, No Cavalry To The Rescue, Only A Cop.” Paul Newman plays “Murphy,” a good-old drunken Irish cop who has delivered 14 babies in 17 years on the job and has a social conscience the size of New Jersey. Corelli (Ken Wahl) plays his well-dressed Italian partner, whose youthful, positive thinking, self-help book reading character stands as a perfect complement to Newman’s rugged, non-conformist veteran. In fact, the movie not only concentrates on how these two battle with the “natives” but also with their fellow officers Morgan (Danny Aiello) and Dugan (Sully Boyar). These two corrupt cops represent the dark side of this precinct – characterized as racist, short-tempered murderers who are casting a bad light on the good cops. Interestingly enough, all of the prominent cops in the movie are either Italian-American or Irish-American, ethnic groups who at one point during the early to mid-twentieth century made up a large part of the South Bronx demographic.

Fort Apache, the Bronx (1981), unlike The Warriors and Times Square, concentrates upon the struggles of two cops on the hostile urban frontier of the South Bronx. The tag line for the movie establishes the figures of the Western frontier if you somehow missed the allusion in the title, “No Cowboys, No Indians, No Cavalry To The Rescue, Only A Cop.” Paul Newman plays “Murphy,” a good-old drunken Irish cop who has delivered 14 babies in 17 years on the job and has a social conscience the size of New Jersey. Corelli (Ken Wahl) plays his well-dressed Italian partner, whose youthful, positive thinking, self-help book reading character stands as a perfect complement to Newman’s rugged, non-conformist veteran. In fact, the movie not only concentrates on how these two battle with the “natives” but also with their fellow officers Morgan (Danny Aiello) and Dugan (Sully Boyar). These two corrupt cops represent the dark side of this precinct – characterized as racist, short-tempered murderers who are casting a bad light on the good cops. Interestingly enough, all of the prominent cops in the movie are either Italian-American or Irish-American, ethnic groups who at one point during the early to mid-twentieth century made up a large part of the South Bronx demographic.

The concentration upon particular ethnic groups within this locale resonates a form of geographical nostalgia, while also suggesting that, indeed, these groups are still there, Murphy and Corelli both live in the South Bronx! And they continually reaffirm throughout the movie that they are trying to keep some semblance of a neighborhood together. The rhetoric of good cop/bad cop drives the narrative of this film, and while this film seems to be, at times, trying to reclaim the heart of the South Bronx by imagining compassion and community, Latino and African-American characters are often portrayed as savage occupiers of someone else’s lost community. When the wilderness of the South Bronx becomes too explosive after the death of a Latino boy (who was murdered by the “bad” cops), the police department goes after Latino and African-American community activists whose “communist” beliefs pose a revolutionary threat to the status quo. This concentration upon the urban frontier and potential insurrection in many ways oscillates between, as Stuart Hall suggests “two alternative poles of containment and resistance” (238). This movie visualizes the containment of the community within the South Bronx through force and repression, while at the same time reflecting the moments of resistance within the community. The presence of social activists and well-spoken leaders contends with the prominent display of pimps, prostitutes and drug-dealers. And while I am not suggesting this movie affords the cops and “natives” equal representation, I believe that the very representational disparity within the movie offers a space for a critique of the ideological underpinnings of the Urban Jungle film.

A case in point is the transformation of Blaxploitation’s own Pam Grier from the independent, socially responsible Coffy (1973), Foxy Brown (1974), and, most notably, Friday Foster (1975), to the doped-up, homicidal hooker who shoots cops for no apparent reason and preys on white men recently stranded off the Cross Bronx Expressway. Grier’s move from Blaxploitation movies (a space where black identity was engaged in a profound struggle with its own representation on-screen) to roles like Fort Apache, the Bronx suggests the ideological transformation from the films of the early1970s to those of the early 1980s. Grier’s character is stripped of the independence and integrity she enjoyed in earlier roles to become a resounding racialized icon of horrific sexuality. In the scene where Grier both seduces and assaults an unassuming suburbanite with a razor blade hidden in her mouth, the victim (a white, male suburbanite, whose car broke down on the Cross-Bronx Expressway) and his bloody fate reinforces the suburban fear of the horrific conditions of the inner city on several levels. On the other hand, this scene simultaneously discloses one of the most prominent reasons for the disinvestment of the South Bronx: the Cross-Bronx Expressway – which runs through the heart of the South Bronx and leveled communities while pushing down land values in the 1950s and 60s. Therefore, while such a ghastly scene as this may encapsulate the means through which the savage, inner city dweller becomes codified within the Urban Jungle movie, it also offers an alternative understanding of how the communities within the inner city have undergone their own infra-structural rape at the hands of progress, development and capital.

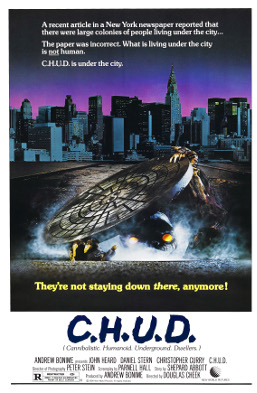

[openbook booknumber=”155652241X”] According to journalist Jennifer Toth’s 1993 book The Mole People, which deals with New York City’s underground population, the acronym C.H.U.D. (Cannibalistic Underground Humanoid Dwellers) is a term coined by a New York City MTA maintenance worker for the subway tunnels’ homeless. Interestingly enough, there is no further mention of the etymology of this term. In fact, Toth notes later on in her book that one of the underground dwellers she interviewed in the early 90s adopted the name C.H.U.D. because he had read it in one of her articles. While I am not attempting to discredit Toth or establish essentialized origins here, it seems much more feasible that both the MTA workers and the subway tunnel inhabitant borrowed this acronym from another source, the 1984 low budget film C.H.U.D. In fact, while Toth’s book was being researched from 1989 through 1992, the filmic figure of C.H.U.D. had already spawned a sequel. I dwell on Toth’s book because in many ways it establishes itself as a journalistic expose of New York City’s literal underworld. However, the film C.H.U.D., close to a decade earlier, had already exposed the community of people living under the city streets to a popular audience. In fact, the pictures taken for Toth’s book might just as well be screen shots from the 1984 film.

C.H.U.D. is probably one of the most memorable bad movies of the 1980s, a time when VHS ruled the land and access to low-budget movies was only a video store away. In fact, a film like C.H.U.D. might not have enjoyed the exposure and modest success had the VCR not been so widely available. Moreover, C.H.U.D. probably would not have been made at all if the VCR was not widely established (but this is an issue for a larger work I have in mind on B-Movies in the 1980s). Let it suffice to say that the widespread circulation of the term C.H.U.D. was predicated on the everydayness of the VCR in the mid-80s. Moreover, the figure of a C.H.U.D. might be as recognizable in a long-line of other contemporaneous film demons, such as Freddy Krueger, Michael Meyers, and Jason. And while all of the aforementioned monsters are amoral psychotics, C.H.U.Ds are anonymous victims, C.H.U.D.s are an acronym, and C.H.U.D.s are a cover-up. C.H.U.D.s are underground “mole people” who were transformed into toxic cannibalistic monsters. The movie is premised on a government cover-up that hides the fact that hazardous nuclear wastes have been buried underneath New York City for years, the effects of which turn the underground inhabitants into man-eating monsters. The acronym title of the film stands for Cannibalistic Humanoid Underground Dwellers, and is itself a cover-up for the government’s top-secret project C.H.U.D., which we discover really means Contamination Hazard Urban Disposal. An alternative reading of the acronym C.H.U.D. opens up some highly suggestive ideas for re-reading what might prove to be the most interesting thing about this film – its title. C.H.U.D. defines a group of man-eating subterranean monsters while it simultaneously defines a covert governmental project to dump toxic waste in New York City’s sewers. And while we can quickly recognize this as a generic B-movie plot of the 1980s (The Toxic Avenger (1984) being another), we might also be able to read the acronym C.H.U.D. as a demonization of the disenfranchised that serves to conceal or suppress other factors that contribute to the perceived monstrosity of the inner city – but as the movie’s tagline warns, “They’re not staying down there any longer!”

C.H.U.D. is probably one of the most memorable bad movies of the 1980s, a time when VHS ruled the land and access to low-budget movies was only a video store away. In fact, a film like C.H.U.D. might not have enjoyed the exposure and modest success had the VCR not been so widely available. Moreover, C.H.U.D. probably would not have been made at all if the VCR was not widely established (but this is an issue for a larger work I have in mind on B-Movies in the 1980s). Let it suffice to say that the widespread circulation of the term C.H.U.D. was predicated on the everydayness of the VCR in the mid-80s. Moreover, the figure of a C.H.U.D. might be as recognizable in a long-line of other contemporaneous film demons, such as Freddy Krueger, Michael Meyers, and Jason. And while all of the aforementioned monsters are amoral psychotics, C.H.U.Ds are anonymous victims, C.H.U.D.s are an acronym, and C.H.U.D.s are a cover-up. C.H.U.D.s are underground “mole people” who were transformed into toxic cannibalistic monsters. The movie is premised on a government cover-up that hides the fact that hazardous nuclear wastes have been buried underneath New York City for years, the effects of which turn the underground inhabitants into man-eating monsters. The acronym title of the film stands for Cannibalistic Humanoid Underground Dwellers, and is itself a cover-up for the government’s top-secret project C.H.U.D., which we discover really means Contamination Hazard Urban Disposal. An alternative reading of the acronym C.H.U.D. opens up some highly suggestive ideas for re-reading what might prove to be the most interesting thing about this film – its title. C.H.U.D. defines a group of man-eating subterranean monsters while it simultaneously defines a covert governmental project to dump toxic waste in New York City’s sewers. And while we can quickly recognize this as a generic B-movie plot of the 1980s (The Toxic Avenger (1984) being another), we might also be able to read the acronym C.H.U.D. as a demonization of the disenfranchised that serves to conceal or suppress other factors that contribute to the perceived monstrosity of the inner city – but as the movie’s tagline warns, “They’re not staying down there any longer!”

These other factors that I allude to might be more apparent when we take a closer look at certain elements of the film. The action of C.H.U.D. is located in the Soho neighborhood of New York City. The first scene of the movie takes place at night on a barren, loft-lined side street of Soho (Lafayette and Spring to be precise), the opening shot focuses on a woman walking her poodle in the middle of the street. The camera is focused on her and the poodle while featuring a sewer cap in the foreground. Lo and behold, as the woman approaches the sewer cap the clawed, slimy, green arm of a C.H.U.D. grabs her ankle and drags her and the poodle into the underworld, leaving only her shoe behind. While this scene might be read as a typical “Urban Jungle” scenario – lone woman at night in big scary city gets killed by toxic mutant – the scene that directly follows might speak more to the issues within this paper. The following scene is a prolonged shot of a New York City street sweeper driving down that same city street, which is littered with trash as well as bums, drug addicts and crazies. The street sweeper swallows up everything on the block, including the woman’s shoe, offering the other side of the Urban Jungle movie, a visualized cleaning up of the city’s “filth.” The relationship between the typical monstrous view of the New York City landscape within the films of the 1980s, and the act of cleaning these streets up is immediately juxtaposed within this film. Moreover, cleaning up the streets of several parts of New York City was in full swing during the early 80s, both the streets of the Lower East Side and Soho were being bought at a discount and sold at a tremendous profit during the “roaring 80s.”

Consequently, the streets of New York City, while still relatively dangerous in the mid 80s, were forcing an entirely different group of disenfranchised New Yorkers underground. During the Reagan 80s, varied social forces converged, resulting in a devastating downward spiral of the economic capabilities of the middle and lower income classes. The aftermath of urban renewal, de-industrialization, de-institutionalization, and Reaganomics left a ruin of homeless people in its wake. In fact, Reagan waged war upon government funding for mental health facilities that resulted in thousands more homeless in New York City throughout the decade, many who were literally and figuratively forced underground. C.H.U.D. might be the only movie in the 1980s that actually suggested that the homeless and disenfranchised New Yorkers were being literally forced out of the light of visibility. The story of C.H.U.D. is possibly the most pronounced and unequivocal indictment of urban reform and renewal within New York City. And while arguing for C.H.U.D.’s reconsideration for an Oscar is not the point here, what is the point is reconsidering the place of C.H.U.D. within a larger genre of urban movies that both document the complex changes within the New York City landscape during the 1980s while offering new ways to read the popular cultural forms of urban gentrification.

Ending this paper after talking about four movies in so short and incomplete a manner is by no means preferable, but to talk about all the possible films that might reflect upon this genre I am trying to establish, as well as the social, political, and economic framework in which they were made, cannot be explored in a paper that is already running too long. Acknowledging this, I will close by suggesting that certain movies during the 1980s (as well as the late 1970s and early 1990s) that deal with New York City often focus specifically upon many of the issues mentioned in this paper, such as urban divestment, gentrification, and demonization of the disenfranchised. Moreover, many of these movies employ popular myths of the frontier and the rugged individual while simultaneously offering more subversive notions such as government conspiracies, organizing against the hegemonic power, revolutionary cultural forms such as punk, as well as sustained critiques of social and economic policy during the 1980s. Films such as Maniac (1980), Alphabet City (1984), State of Grace (1990), King of New York (1990), The Wanderers (1979), The New York Ripper (1982), Manhattan Baby (1982), Do the Right Thing (1989), New Jack City (1991), Fresh (1994), Blue in the Face (1995), Smoke (1995), and Candyman (1992) might all fit into a larger umbrella of urban films in the last 25 years that deal with many of the concerns of this paper. And while this list is just getting started, I think that Michael Denning’s call for a Marxist revision of American culture is already underway (his own Mechanical Accents might be an prime example). And a more focused cultural, economic and historical look at the production and distribution of these movies, in addition to their assorted and often prophetic readings of the gentrification of Urban landscape, would add yet another voice to the ongoing struggle over the readings of the popular within the contemporary – but not because its Popular Culture, but because within all facets of culture there is the record of a struggle between those in power and those subordinated to that power. Otherwise, it might seem ludicrous to write about C.H.U.D. and Marxism with a straight face.

I admit, I didn’t read the whole thing … but I bet your old paper didn’t have youtube clips throughout to bring the real story to life! Another amazing reason this is the publishing medium of the future to me. If all articles read like a production I’d be thrilled — remixing is the new composition.

I am thrilled you posted this. I, too, struggle to live in spite of The Simpsons. Can’t wait to sit down and read in full…

This is something I will come back to & digest in snippets over the next 4-12 years of my life, I guarantee it. Mostly because I am predicting I will disagree with you on a lot of it. And that excites me to no end.

Oh wow. I remember you writing this thing as well as your panel. Great stuff then, great stuff now. The media enhancements work very nicely. Will reread and engage.

You had me at “exceptionalist paradigm.” I heart American Studies.

It’s going to take me a few days to find a block of time to read this piece, but it looks very interesting. Thanks so much for sharing it here!

Frankly, I think you’re all masochists, but thanks for the encouragement. I hope it isn’t used against you in the end, because it will mean I will publish more long stuff (and I have tons). This paper is an aberration, but an experiment as well in terms of new media “papers,” but I can’t believe the first 8 pages won’t put most people to sleep, it is the traditional I need to quote theorists and explain them rather than weaving their ideas into a bigger whole. I think everything in the first part could have been far more concise and textured by laying it on top (or side-by-side) with the film discussions. This was just the easiest way to lay it all out, but certainly no the best.

But anyway, thanks for the kind words, and you’re a nut if you read it 🙂

Nice take on the “nightmare” version of James Sanders’ “dream” city. (His “Celluloid Skyline” has spawned a pretty interesting web version: http://www.celluloidskyline.com/main/home.html ). IMO, your best sentence is: “[Urban jungle films] often reflect a kind of struggle at work within the invisible underworlds and subcultures of any given city that is akin to a city at war with itself, factions of power (wealthy developers, the agents of gentrification, the minions of capital) versus those being marginalized, displaced, and dis-empowered.”

Two things: you’ve got to include Wolfen (1981) – – which seems to mingle all the motifs – – monsters, South Bronx, ghost lore, urban warfare, inter-racial brotherhood fantasies, precocious-Predatorism, etc.; and, you reminded me why I enjoy Richard Price’s stuff so much – – from the novel version of Wanderers through his screenwriting and into Lush Life – – his effort to keep alive (often with pretty rough results) that old social-democratic vision of working-class NYC . . .

L Hanley,

Thanks for the comment here, and I have to say I write about a lot of stuff, but nothing is dearer or nearer to me than movies, NYC and reading culture through film. And your recommendation for Wolfen is perfect, and I do agree with you about the quote, it is one of the few places in that bloated 20 or so pages where I boil it down, but that was a grad school paper, with all the associated virtus (research and time to thing) and flaws (convoluted and often strained language). Never been much of a write in terms of succinct and clear prose, so seeing someone point a phrase out makes my day. As for Richard Price, did you see his cameo in The Wire, which seems to deal with all these issues much more directly now that thy have already happened:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1M2AUYYKfxk

Now that is an awesome scene, and I think making the triangulation between NYC in 70s and 80s film, The Wire, Rick Prelinger’s work on Detroit, and perhaps kick it back to Fassbinder’s “Berlin Alexanderplatz” or even Francesco Rosi’s “Hands over the City” a openers….could be a fun class.

Great Wire clip! (Pop culture’s scens of teaching/professing are rich and thick, caloric guilty pleasures! And, Mr. Price’s class is a pedagogue’s dream – – calling all Freirian ghosts!.)

Agree with your fun class! (In an Am Studies class on NYC, I once included a unit on “Necropolis”(http://hanley.wikispaces.com/IntroAmStud) – – NYC in the 1970s – – but it was anemic and rushed.)

Some additions following up your Prelinger/Fassbinder/Rosi:

Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Camilo Jose Vergara, American Ruins (http://amzn.com/1580930565)

Jack Kugelmass, Miracle on Intervale Avenue: The Story of a Jewish Congregation in the South Bronx (http://amzn.com/0231103077)

Seymour Perliin’s “Lost Civilization of the Jewish South Bronx” website http://www.bronxsynagogues.org/ic/bronxsyn/synopsis.html)

Jonathan Mahler’s book, Ladies and Gentlemen, the Bronx is Burning (not the crappy ESPN version)

Later takes on the theme: Mimic (1997) [update of C.H.U.D.] , Jeff Stanzler’s 1992 flick, Jumpin’ at the Boneyard

And, John Kossik’s homegrown website (on Detroit), 63 Alfred Street: Where Capitalism Failed (http://www.63alfred.com/)

Beware – – you’ve unleashed the “dream course” syndrome – – the academic version of Nakata’s Ringu.

PS Wolfen scene dubbed into German (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FsoKU2i65zE) – – Fassbinderized to eerie effect!

All right L Hanley,

This is getting too fun and between the list of books and films you provided in these comments you have created a compelling syllabus already. So here’s my question: how do you and I propose this as a course somewhere and actually teach, along with getting paid (the more difficult reality these days).

Well, I guess we could just continue to blog and write about it which is similar and has obviously brought us together in unexpected, but quite fortunate, circumstances.

We could call it something like NYC as scene by film: 1965 to Now)?

I do’t know I am just throwing this out, but this has been awesome, and I guess I need to either build on it make something fun of it, or continue to glare at this screen in front of me longingly…and then just give up and buy an iPad and never create anything ever again 🙂

Pingback: Can you dig it? Is The Warriors culturally significant? | bavatuesdays

Pingback: C.H.U.D. Sundays at Reclaim Video | bavatuesdays