As of late my two year old son, very soon to be three, has eschewed all forms of narrative video on YouTube. He’s dispensed with the Thomas the Tank Engine scam (that series is all about being a useful worker, akin to 19th century British imperial labor propaganda), and has opted for simple videos people have posted of trains passing by while they’re waiting to cross the tracks. One of his favorites is this minute-long video of a train crossing in Roberts, Oregon:

I’m often sitting right next to him while he spends time whipping around YouTube looking for trains, and what struck me about the above video is the number of views it has: 21.5 million. Let me say that again: 21.5 million views. Insane! What it got me thinking about is how many people might be doing just what my son is, cruising around to watch these videos that are non-narrative. In fact, it reminds me of this post I wrote back in 2008 when I was describing the magic of Ray Harryhausen’s animations in the original (and in my heart only) Clash of the Titans (1981) as attractions in and of themselves, almost extra-narrative. It was a riff on film historian Tom Gunning’s idea of a “Cinema of Attractions.” His theory suggests there were myriad non-narrative forms of cinema from 1895-1908, but as the dominant Hollywood narrative began to congeal from 1910 to 1917 (famously cemented in 1917 with the cinematic grammar of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation) the almost constant state of transformation of the medium for its first twenty years began to ossify into a much more linear and delimited narrative style. To quote Gunning:

[Cinema prior to 1908] did not see its main task as the presentation of narratives. This does not mean that there were not early films that told stories, but that this task was secondary, at least until about 1904. That transformation that occurs in films around 1908 derives from reorienting film style to a clear focus on the task of storytelling and characterization.

Rather than using film for outright entertainment purpose, the “cinema of attractions” offers the viewer something different: “the chance to take a journey somewhere else-a place to which he will likely never physically travel…films sought to transport the viewer through space and time, rather than to simply tell a story,” as Lila E. Stevens points out in her discussion of documentary film here. This idea strikes me as akin to a way of understanding the emergence of the visual vernacular and minimalistic design impulse of the web more recently. The web is in many ways an internet of attractions more than it is a medium germane to more traditional narrative forms that we have come to expect given our immersion in 20th century film, television and radio.

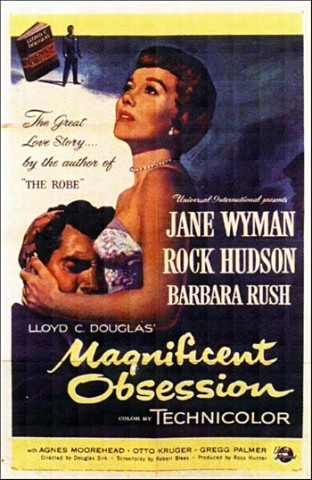

Some of the criticism about ds106 I’ve heard over the last three years as a course has been it doesn’t spend enough time on the the actual storytelling—which I read as more traditional ideas of digital storytelling. When I started preparing the first ds106 course in 2009 the idea of digital storytelling was often associated with the slideshow made in iMovie featuring the Ken Burns effect set to your favorite song about a moment that’s “changed your life.” I know this is an over simplification, but at the same time that’s still the model set forth as digital storytelling. I pretty consciously wanted to eschew that like my son began avoiding Thomas the Tank Engine videos. I wanted to explore the internet of attractions: the idea of digital representation, experimental sound, video essays, movie posters, animated GIFs, etc, as the non-narrative forms that we are communicating with on the web.

Heretofore I’ve been arguing around this point suggesting that these are stories too, but in many ways that was a cop out. They aren’t stories in the same way we have come to expect narrative from television, film, and radio—and in many ways that is why I was attracted to them and why ds106 moved further and further away from the idea of storytelling as we’ve known it. The internet of attractions is a compelling frame to start understanding the emergence of a web-based vernacular that isn’t “digital storytelling” per se. I haven’t even begun to discuss how this is also dependent upon a much larger context of interacting and playing within pop culture allusions. This idea of the Internet of Attractions is obviously still quite raw in my mind, but it is the first useful quasi-theoretical frame I’ve come up with to start understanding how what we are doing when we communicate on the web with pictures, GIFs, design assignment, quick photoshops, sounds, etc. is not exactly digital storytelling as it is currently being understood.

Tonight’s class was a bit low energy given how late we are in the semester and how much reading I have thrown at the #emoboilers—but as they say what doesn’t kill you just leaves a vicious scar. Early on during our discussion of Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia it was painfully apparent how few students had actually done all the reading, for shame! Nonetheless, the discussion was still quite interesting, at least for me, because we covered a few very big and important themes running through the novel.

Tonight’s class was a bit low energy given how late we are in the semester and how much reading I have thrown at the #emoboilers—but as they say what doesn’t kill you just leaves a vicious scar. Early on during our discussion of Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia it was painfully apparent how few students had actually done all the reading, for shame! Nonetheless, the discussion was still quite interesting, at least for me, because we covered a few very big and important themes running through the novel.